Arrival in Dallas

From Perspectives Part II:

In 1984, the medical center looked to strengthen its molecular biology expertise, especially in the area of gene cloning, because the process had become a critically important component of biomedical research.

The medical school was on the hunt for a Chairman of the Department of Biochemistry, which took Joe Goldstein, MD, to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories in Long Island, New York — a place Mike Brown, MD, once described as being to biology “what Athens was to philosophy.” There, Goldstein met with Joseph Sambrook, PhD.

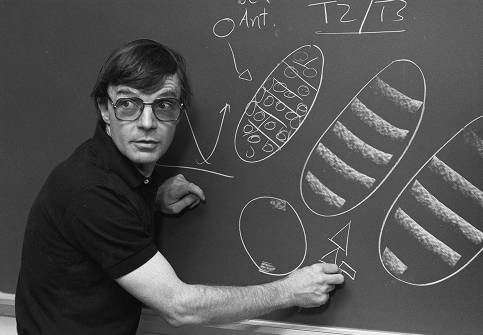

Sambrook was a British molecular virologist, internationally known for his work with the genetics of DNA tumor viruses and how they integrate their DNA into a host cell. He had been personally responsible for many of the advances in molecular biology technique and had co-authored the definitive manual on gene cloning.

In short, Sambrook was exactly who the medical school needed.

While there was little doubt that Sambrook could propel UT Southwestern to the leading edge of molecular biology, few thought he would leave the academic environment offered by Cold Spring Harbor. Sambrook had been personally hired as assistant director there by James Watson, MD, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, and was the logical choice to succeed him.

UT Southwestern invited Sambrook to spend time on campus beginning in September 1984. During his time in Dallas, he witnessed the level of community support given to the molecular biology department through a significant, anonymous gift donated through Southwestern Medical Foundation. It made an impression.

“The standard of science here is very high,” Sambrook noted, “and the people have a great desire to have the place be number one.”

He accepted the position as Chairman of the Department of Biochemistry on August 1, 1985.

Influential Progress in Genetics

Dr. Sambrook came to Dallas knowing there were people here with the same hunger to put UT Southwestern on the map with breakthroughs in medical science, human genetics, and transformative technology. His research team at UT Southwestern invented and secured a patent for the first second-generation drug, tissue plasminogen activator (TPA), a life-saving thrombolytic therapy – and the first realization of the promise of genetic engineering – that is still used in clinics today for heart attack and stroke patients.

Dr. Sambrook was the driving force and senior author of four editions of the best-selling, highly influential science text, “Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual.” He is internationally renowned for his studies of DNA tumor viruses, has made important contributions to the understanding of intracellular trafficking and protein folding, and was an influential leader in the field of the molecular genetics of human cancer.

UT Southwestern colleagues describe Dr. Sambrook as a trailblazer, always at the front of the pack, leading and recruiting scientists to the Department of Biochemistry and to the Dallas branch of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Three of those HHMI scientists would go on to win Nobel Prizes.

Recruiting and Matchmaking

In early 1988, Dr. Sambrook recruited Dr. Johann “Hans” Deisenhofer, who would go on to receive a 1988 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research that explained the detailed mechanism of the first steps of photosynthesis. He was also responsible for introducing Deisenhofer to his future wife, Dr. Kirsten Fischer-Lindahl.

From Perspectives Part II:

“I received a formal letter from Joe Sambrook (whom I had never heard of) asking whether I might be interested in a faculty position,” Deisenhofer said. “I knew absolutely nothing about the place…but a postdoctoral fellow in our research group in Munich had completed his PhD at Baylor College of Medicine in Houstonand spoke highly of UT Southwestern.”

Deisenhofer ended up visiting the campus twice.

He was impressed by the breadth and depth of the school’s basic sciences department and the spirit of collaboration that existed between it and the clinical departments, and he recognized the benefits of being a Howard Hughes Investigator.

During both visits, Sambrook fortuitously asked Kirsten Fischer-Lindahl, a Professor of Microbiology and Biochemistry and a Hughes Investigator, to show Deisenhofer around Dallas. “Almost immediately after I met her, I fell in love,” Deisenhofer recalled.

In March 1988, Deisenhofer moved to Dallas to become a Professor of Biochemistry at UT Southwestern and Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

In December, Deisenhofer, Michel and Huber received the 1988 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.

Fischer-Lindahl and Deisenhofer were married in 1989.

We at the Foundation offer heartfelt condolences to family and friends of Dr. Sambrook. It is our wish and honor to ensure that his legacy continues to be remembered by our community and future generations of scientists at UT Southwestern.