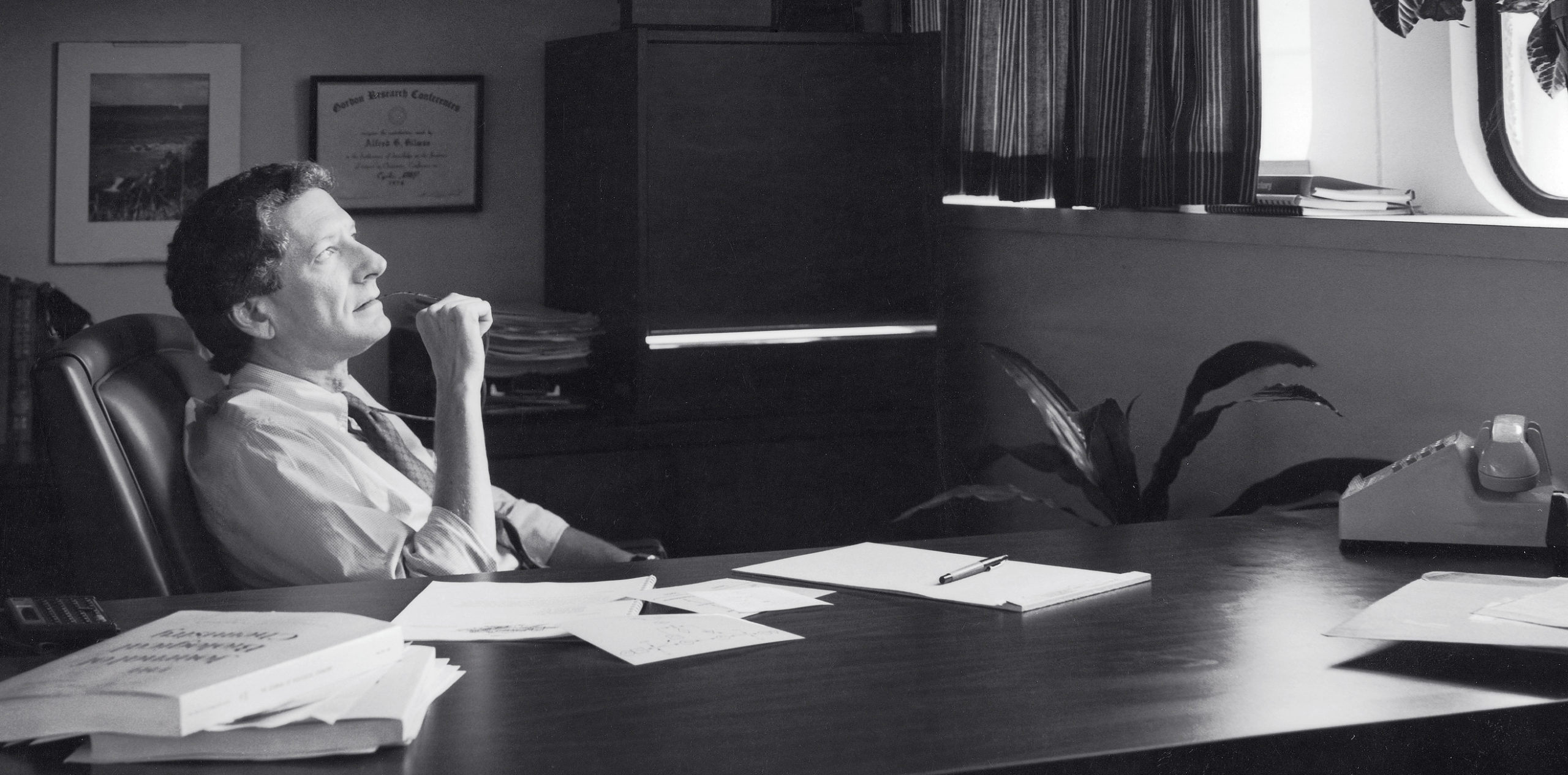

Great intellect, dogged determination and relentless curiosity were rewarded on October 10, 1994, when the Nobel Prize Committee announced that Alfred G. Gilman, MD, PhD, Chairman of the Department of Pharmacology, had won the 1994 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of G-proteins and the role they play in cellular communication.

He shared the prize with Martin Rodbell, MD, at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in North Carolina.

Gilman had maintained his intense focus over the course of three decades, earning him election to the National Academy of Sciences (1985), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1988), and the Institute of Medicine (1989) and garnering him the Lasker Award (1989), among others.

But nothing quite compares to becoming a Nobel Laureate.

“Someday you’ll be able to design a drug that works on only the molecule you want to target and on no other molecules in the human body,” Gilman predicted at the time.